DVT Exam

In addition to taking a history, we will also perform a Physical Exam where we examine the legs and determine how much swelling we see, presence or absence of visible varicose veins, tenderness in the calf or deep thigh, redness of the skin, or signs of long-standing venous insufficiency.

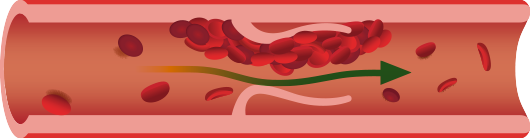

A venous ultrasound is performed where we image the veins in the legs and determine if a blood clot is present. If a DVT is present, we generally consider if it is just a smaller vein below the knee (an isolated calf vein thrombosis, or ICVT), if it is above the knee (a femoral popliteal DVT) or if the clot extends from the lower leg into the pelvis (an iliofemoral DVT).

This information helps us assess what treatment options are indicated, and if so, for how long.

When a DVT is suspected or diagnosed

We begin by taking a detailed history to determine DVT treatment options:

- What is the patients age?

- How much swelling is present and is it getting worse or better?

- Does the patient have full mobility, partial mobility or very limited mobility?

- Is the leg immobilized in a cast?

- Was there a history of injury or surgery?

- Regarding surgery, did the patient have: Hip or knee replacement? Broken hip, pelvis or leg? Serious fall with broken bones? Spinal cord injury resulting in paralysis?

- Is there a history of stroke?

- Does the patient have a history of cancer or other medical conditions such as kidney failure?

- Does the patient have a prior history of DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE)?

- Does the patient have a family history of blood clotting disorders?

Call 1-800-834-6362 to Schedule a Consultation or Use Our

Provoked vs Unprovoked DVT

Part of the assessment is to determine if the DVT is what we categorize as “Provoked” vs “Unprovoked.” Provoked DVT occur as a result of a major risk factor, such as recent surgery or trauma or a major medical problem such as kidney disease or cancer. These risk factors can be transient or not. In transient cases, such as after surgery or trauma, once the risk factor goes away the risk of recurrence after stopping anticoagulation is very low. Patients with unprovoked DVT do not have a readily identifiable risk factor that likely contributed to their DVT. These are patients who develop DVT “out of the blue” so to speak. These patients have a higher risk of recurrence of DVT after anticoagulation is stopped. Patients at the highest risk of recurrence are those with a provoked, but not transient risk, such as those with cancer.

Treatment for DVT

The treatment is influenced by what we learn in the history, sete on the physical exam, and learn from the ultrasound. Generally, for starters, we advise nearly all patients to consider graded compression hose. This can help reduce swelling and thus reduce pain in the early days.

Anticoagulation Medication

In many cases we advise a therapeutic regimen of anticoagulation. These are drugs to thin the blood. This is usually with a medication like Xarelto (rivaroxaban) or Eliquis (apixaban), but could also be coumadin or warfarin. Occasionally, we prescribe low molecular weight heparin (ie Lovenox), which is a shot, especially around the time of surgery. We discuss the pros and cons with the patient to determine the best medication for their circumstances. Ideally the patient is started on one of these drugs right away unless there is a high risk of bleeding. The location of the DVT and other factors can also influence the treatment plan for DVT:

Length of Anticoagulation: Most patients with a first time, provoked DVT, will need therapeutic anticoagulation (ie blood thinners) for about 3 months. This is discussed in the consultation with the care providers at the time of diagnosis and in follow up visits. Some patients will need to stay on anticoagulation medication indefinitely. The decision to extend anticoagulation beyond 3 months indefinitely is usually made in consultation with a hematologist who can do some testing to determine the patient’s risk for long term recurrence of DVT.

In summary, patients with provoked DVT or PE with transient risk factors (such as surgery or trauma) have a low risk of recurrence. Patients with unprovoked DVT or PE have a higher risk of recurrence.

Patients with provoked PE or DVT with persistent provoking risk factors (such as ongoing treatment for cancer) have the highest risk of recurrence if the anticoagulation is stopped.

We often work with the primary care doctors and hematologist to help advise if in cases where recurrence risk is high, the patient should perhaps stay on anticoagulation for longer or even indefinitely.

Patients at higher risk for recurrence long term are those that have:

- An unprovoked DVT or PE without associated risk factors

- A DVT or PE even with risk factors, but at a young age (i.e. less than 40)

- Recurrent DVT or PE, especially at different sites

- Family history of DVT or PE at an early age

- Thrombosis in unusual locations (like in the veins to the intestines or the arm)

Bleeding and Anticoagulation

All of the blood thinners have a risk of bleeding. This risk of bleeding is higher in patients with a recent history of surgery or trauma, or in patients with known bleeding issues (like bloody nose, bleeding stomach ulcers, stroke, etc.). Age is a risk factor (greater than 65) and use of alcohol. ( more than 8 drinks a week).

Patients with medical issues are at higher risk of bleeding (including high blood pressure, kidney disease, liver disease, stroke history) as are patients with known prior bleeding issues. The use of aspirin, platelet inhibitors like clopidogrel (Plavix) or non steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDS) such as ibuprofen or Aleve may also increase the risk of bleeding while on anticoagulation.

We generally advise also checking with the doctors who prescribed these medications to determine if they can or should be continued while the patient is on anticoagulation. Patient specific risks and benefits of anticoagulation must be carefully weighed in all patients who are potential candidates for long-term anticoagulation therapy. If any signs of bleeding occur while taking an anticoagulation medication, the patient should seek medical evaluation immediately.